Goal

Increase funding for state fish and wildlife agencies to tackle the many challenges of wildlife conservation for today and into the future including fully implementing their State Wildlife Action Plans.

State fish and wildlife agency budgets fall vastly short of the needs of wildlife. Nearly all agencies still rely on hunting and fishing user fees, instead of support from all citizens who all benefit. It is time for greater and more diversified funding. Only then our agencies can fully meet the needs of all wildlife and all its citizens. Several states serve as models, with Georgia in 2018 finding success with the dedication of an existing sales tax on outdoor recreational gear, generating more than $20 million per year to several conservation needs that include wildlife. This section explores the limits of current funding and recommends a path towards robust, reliable, diversified and public financing. The Georgia model is recommended as the most likely to succeed.

Current Funding

Collectively, state wildlife agencies annual budget is around $5.6 billion collectively. Of this, agencies receive $3.3 billion is from hunting and fishing-related activities, either directly through the sale of licenses, tags, and stamps, or indirectly through federal excise taxes on hunting, recreational shooting, and angling equipment. Many states rely only on these hunting and fishing funds with a few states generating additional significant funding from a dedicated sales tax (e.g. Missouri, Arkansas, Minnesota) or dedication of the existing sales tax from outdoor gear (GA, TX, VA). The hunting and fishing dollars are, in almost all states, the only source of reliable and substantial funds. Other funding comes from a variety of sources at the state level, including general funds, lottery funds, portions of state outdoor gear taxes, real estate transfer fees, income tax checkoffs, sales of wildlife license plates, a mix of federal grants, and even voluntary donations (NH and GA). On average, about 10 percent of an agency’s budget for fish and wildlife conservation and law enforcement activities funds conservation for species that are not hunted or fished—typically referred to as “wildlife diversity” or “nongame” programs. For a complete list of case studies, see additional resources below.

Move Beyond the “Bake Sale” Approach

To fund wildlife diversity programs, states rely primarily on a bake sale approach. Funding often comes from voluntary income tax check-offs and purchases of wildlife vehicle license plates. For example, Texas Parks and Wildlife now features a menu of conservation license plates. Purchase of a plate from the “Wild for Texas Collection” of a hummingbird, rattlesnake and horned toad helps fund the State Wildlife Action Plan. Georgia hosts a very successful and popular Weekend for Wildlife. These voluntary contributions remain important, but they are not sufficient or reliable or fitting for wildlife and the agencies that serve as a public trust.

User-Pay, User-Benefit Model Success and Limitations

The user pay–user benefit approach to funding wildlife conservation has resulted in terrific success stories for many game species, like waterfowl, upland game birds, deer, elk, and sportfish like bass and trout. Because all species need healthy and plentiful habitat, the traditional game-focused funding for wetlands, grasslands, rivers and lakes has benefited a range of wildlife.

However, when it comes to conserving specific wildlife species not hunted or fished for, biologists need to know basic information like their populations, locations, preferred foods, and more. Without this important natural history, the most urgent, priority actions can’t be determined for particular species as they begin to decline. The lack of funding and focus often results in discovering too late that a species is in dire straits, after populations have dropped so low they are at risk of extinction. Some of this valuable information can be found in State Wildlife Action Plans, but there is no funding to take the identified actions.

In addition, hunting and angling no longer assures adequate funding even for game species. Declines in hunting over the last decade, and in certain states, a drop in fishing participation, results in less funding from sales of licenses, stamps, and gear. State agencies must seek more funding sources to effectively manage plants and wildlife and to better focus on the needs of all wildlife and all people. On top of inadequate and declining funds, the earth’s rapidly changing climate is adding to the complexity and urgency to assure our wildlife and the habitats they depend upon will be as resilient as possible.

Need for diversified funding

In a prior section, we introduced the concept of a shareholders meeting that reports on investments and builds trust. Just as investment portfolios aim for diversification, reliability and growth, so should state wildlife funding sources be diverse, reliable and able to meet the increasing challenges of the future.

Fewer than 10 percent of state fish and wildlife agencies have budgets that include funds from their state legislature, commonly referred to as the “general fund” (the overall state budget that comes primarily from taxes). Many also rely on various federal grants and other impermanent, and thus unreliable sources. While some agencies have made strides toward expanding and diversifying funding sources, all state wildlife agencies lack the full capacity to carry out their responsibilities under the public trust—managing so all wildlife can thrive in this and in future generations. As we know from State Wildlife Action Plans, more than 12,000 animals and plants are in need of proactive conservation.

At the national level the federal State Wildlife and Tribal Grants program has been a great start toward bolstering wildlife diversity budgets. The State Wildlife and Tribal Grants program is the only federal program explicitly dedicated to preventing species from becoming endangered. The grants program is able to partially fund the plans, but does not provide nearly enough to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Since 2001, states have received altogether more than one billion dollars. That sounds impressive, yet the average is $60 million per year, spread over 50 states, and Puerto Rico, District of Columbia and all U.S. Territories. That’s far short of the estimated $1.3 billion annually necessary to protect species from becoming endangered now and into the future. On average, states need 10 times more funding than the State Wildlife Grants program offers to solve the wildlife crisis. The key is prevention to avoid much higher costs and permanent losses of our priceless wildlife and habitats.

A growing coalition of wildlife interests is now working on the passage of the federal Recovering America’s Wildlife Act which would, as proposed, provide $1.3 billion/year (see your state here) in annual funding back to states to prevent wildlife from becoming endangered. Enacting the legislation would be a huge step forward in addressing the wildlife crisis. This bill requires every state to come up with a 25 percent match to receive the new federal funding. Therefore, each state needs to find additional funding for the match.

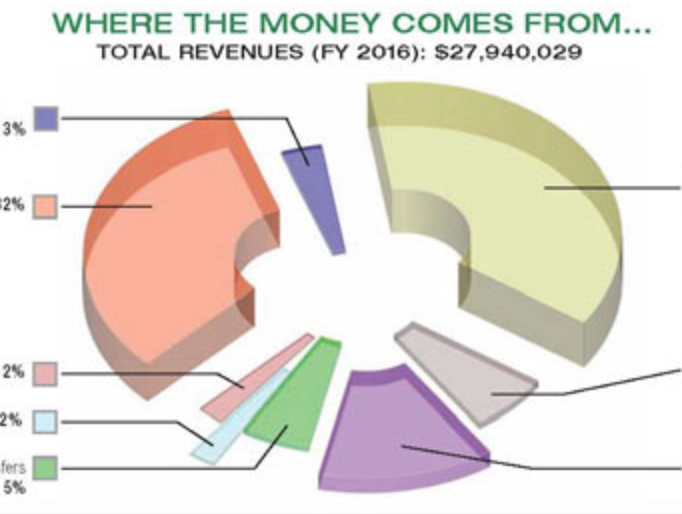

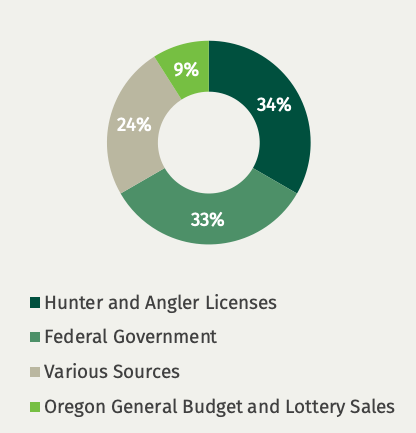

Example of typical agency funding:

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

A third of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s budget comes from sales of hunter and angler licenses, a third from the federal government—most tied to the sale of hunting and fishing equipment. The remaining third comes from a variety of sources, most tied to specific purposes in grants, contracts, or statute. Despite ODFW’s task to manage wildlife for all Oregonians, only a small percent of its budget comes from the general budget and lottery sales combined.

New Hampshire is similar with only three percent of the funding coming from the state’s general budget. The Nongame and Endangered Species Program is provided $50,000 from this general budget but must match it in private donations, effectively acting like an NGO in raising its own funding.

Reliable Funding Mechanisms

Restoring wildlife can take decades of investment. Unlike funding the building of a new hospital over a five-year period, assuring wildlife recovers and thrives takes time. Further, wildlife once recovered still need our attention and care, especially in a rapidly changing climate. The return of America’s symbol—the bald eagle—took decades of effort and shows why investing in a future for wildlife matters, The bald eagle’s future depends on our continued stewardship of the clean waters, fisheries, and habitat. Read the NWF blog here.

The good news is that some states have moved beyond the bake sale approach toward reliable funding. Funding mechanisms include sales taxes (Missouri, Arkansas, and Minnesota), real estate transfer taxes (Florida and South Carolina) and dedicated lottery funds (Arizona, Colorado, Maine, and Oregon). Nevada’s $27.5 million bond program is slated for acquiring wildlife habitat and enhancing recreational opportunities related to wildlife. Georgia, Texas, and Virginia took the user-pay, user benefit traditional model and applied it to a range of outdoor gear that includes all outdoor enthusiasts, without creating a new sales tax. Iowa passed an initiative that assures the next tax increase will give the Iowa Department of Natural Resources a portion of the proceeds. Missouri is considered the pioneer having this program since the 1970’s, see their agency budget in their annual report here.

Public Financing for Wildlife

The time has come for public financing in all states in keeping with wildlife as a public trust. As we’ve stressed repeatedly, states must have resources to conserve the thousands of wildlife species and their habitats they are mandated to protect. The simplest way to secure public financing, although not necessarily the most reliable, is for a state governor to include funding for the agency in his/her budget. The legislature would then need to approve it. This is how most government agencies are funded and likely how most citizens in a state assume their agency is funded. Even minimal general funds to start would be a good foot in the door. Convincing a governor to allocate funds might take repeated efforts, as most state legislatures are not used to providing wildlife funding. By elevating the wildlife crisis, the stage is set for making the case for general funds.

Some agencies might be reluctant to go with the governor’s budget approach, as it gives the legislature more control over the agency in contrast to user fee funds that usually do not require legislative approval. However, a strong coalition can both advocate for the funds and monitor the legislature’s actions.

Articulating the case for funding and building strong partnerships are two key challenges. Partnerships should unite state wildlife agencies and sportsmen and women with all who support strengthening fish and wildlife agencies. Again, find the common ground for the funding case. The hunting and angling community will benefit from new sources of funding that enhance wildlife and their habitats. Much of the on-the-ground conservation action will include securing more habitat, benefiting both game and all other wildlife. More habitat translates into more access for all wildlife recreationists. Funds could also go toward conservation education for the next generation of conservationists.

Ultimately, when all people contribute, all wildlife profits from more habitat and all people profit from more access to outdoor recreation and assurance that our next generation will carry the conservation torch forward.

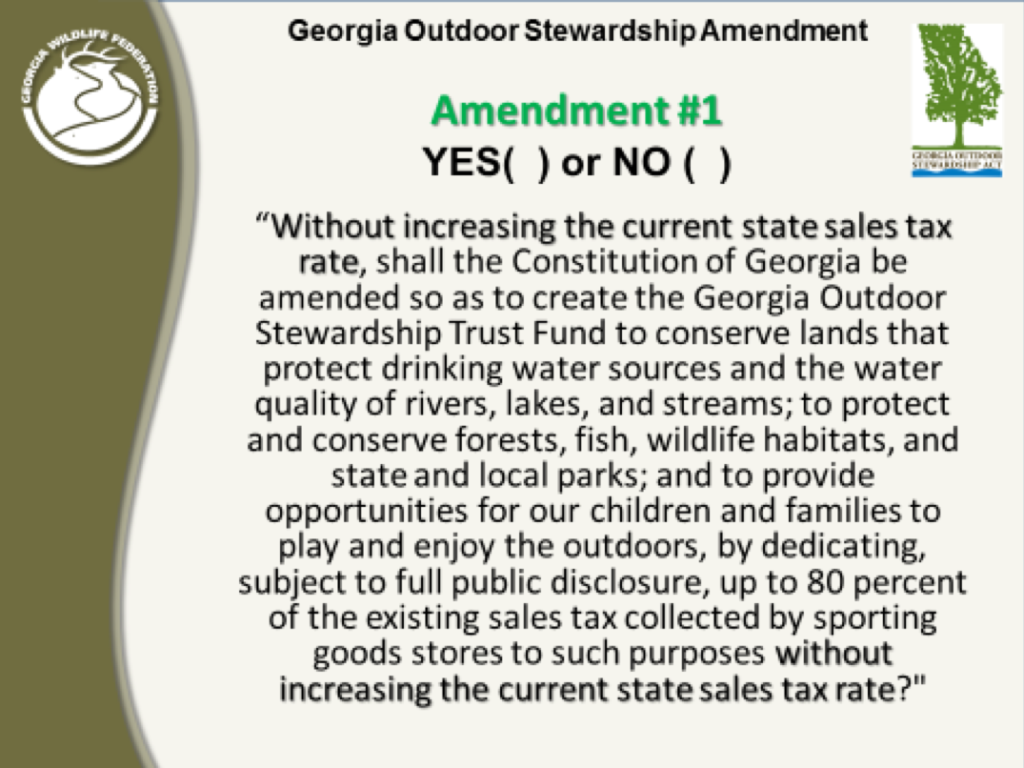

Georgia Outdoor Stewardship Act 2018

This legislation was offered as an amendment on the state ballot in November 2018. It had already garnered support from nearly 100% of the state legislature and polls showed 80% support from the voting public. It took 7 years of work to build this support and included a coalition of the Georgia Wildlife Federation, The Nature Conservancy, Trust for Public Lands, Park Pride, The Conservation Fund, and the Georgia Conservancy. The coalition made the case that conservation creates more jobs and revenue than cotton or any sports team in the state.

The amendment called for up to 80 percent of the state sales tax already collected on the purchase of outdoor sporting goods and recreational equipment be dedicated to conservation funding. See the exact language below.

Texas and Virginia’s Outdoor Equipment Sales Tax

Texas (1993) and Virginia (1998) each passed similar legislative bills dedicating a share of the existing state sales taxes collected on outdoor gear to wildlife conservation. In 2019 Texas passed Proposition 5 expanding this to parks. Rather than creating a new tax, spending estimates (based on National Survey of Hunting, Fishing, and Wildlife Related Recreation spending in that state) are used to allocate a share of general revenue to wildlife accounts. Spending on wildlife conservation is justified as user-pay–user-benefit model, without the administrative burden and potential opposition that comes with a separate tax.

While successful in many ways and important, unfortunately the revenue stream has not been consistent. Texas capped revenues at $32 million per year and then diverted some of that to debt service. Virginia’s legislature allocates its fluctuating amounts to be under a $13 million/year cap, and also does not allocate any other general funds to Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

Nevertheless, this mechanism is considered as the most likely to succeed, as Georgia just proved. For those states with a sales tax, this is highly recommended. Dedicating a share of sales tax revenue does not increase taxes and the data justifies re-investing outdoor gear related fees back into wildlife, land and water.

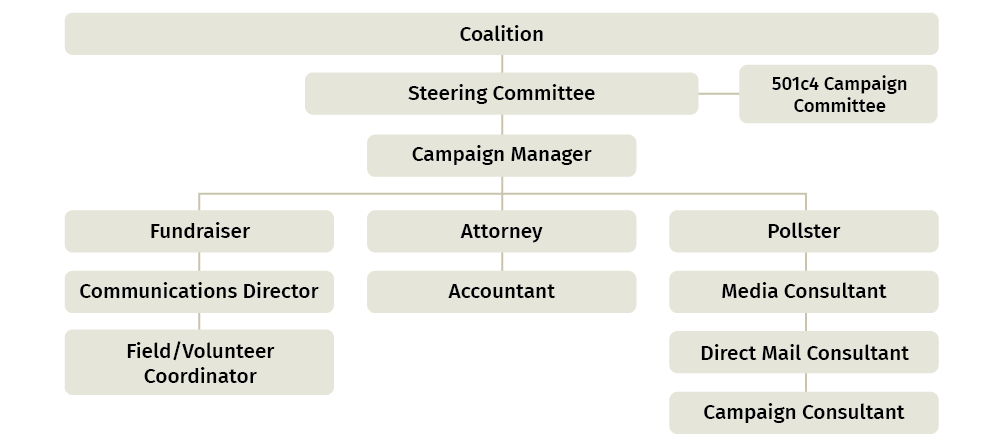

Making the Funding Case—Leading a Campaign

The campaign is the heart of the action. It stands or falls on the strength of your coalition and public support. The likelihood of success is highest when you have good research to back your communications and messaging, strong partnerships developed through a coalition, and support of your state agency, and your governor and key legislators.

What gets groups excited to join your campaign and associated coalition? Likely, it’s increased and reliable funding for wildlife and the outdoors. As we’ve noted, your funding campaign will succeed with a strong coalition in place, widespread public recognition of the wildlife crisis, and an inspired state wildlife leadership.

For an outstanding toolkit on campaigning for conservation funding, please refer to the Campaign Toolkit from Trust for Public Lands Action Fund (The Nature Conservancy and the Trust for Public Land team up regularly, with other state based entities like NWF affiliates, to lead ballot and legislative funding campaigns). They have developed a multi-phase technical assistance approach that includes the following elements:

- Feasibility Research

- Public Opinion Polling

- Program Design

As you go forward, keep these questions at the forefront:

- What factors in your state must you consider when choosing a funding mechanism?

- What is achievable?

- What does success look like?

- What is your clear, organized plan for success?

- Are you building public support at every step?

- Are you proactively defusing opposition and clearing obstacles?

To secure wildlife funding, we break this section into three steps — form a wildlife funding task force, enlist state legislators and governors as champions, and then lead the campaign. Find tips, more case studies, and useful materials at the end.

1. Form a state-based wildlife funding task force

A task force on state wildlife funding immediately elevates the wildlife crisis as an important issue. The task force makes recommendations on funding needs and mechanisms and creates a credible report on why your agency needs the money, how much, and where it should come from. It also creates ambassadors for the associated campaign.

Who establishes a task force? Coalition, Legislature, or Governor

Your coalition itself could establish a funding task force

or a similar panel. That was the strategy of the Blue Ribbon Panel on

Sustaining America’s Diverse Fish and Wildlife Resources—leading to the

introduction of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act.

The advantage is that you can pick your own members. See who they included and

their final recommendation.

Preferably, a state task force can be ordered by a legislature or a governor, depending on who might be most supportive. While you have less say over the makeup, you can advocate for who should be on it. There are three main advantages to going this route. First, it shows the legislature or governor are convinced the issue is so important it merits a task force. Second, a task force develops recommendations that come back to the governing body for action. Third, the legislature might provide funding to support the task force (e.g. Oregon).

Composition of Task force

On the task force, you will need experts in funding, wildlife, and outdoor recreation, representatives of different constituencies and outdoor businesses, members with political influence, and ambassadors that can make the eloquent case for the recommendations. The key is to represent a range of stakeholders and not favor one outdoor recreation or wildlife sector over another.

A state task force typically ranges from a handful to a dozen or more people. They merge their different skills, viewpoints, and ideas to come up with credible recommendations that will be well received across a broad spectrum of interests. (Examples from Oregon, Wyoming, Washington).

To be effective, the group should have reasonable deadlines to conclude work and a specific charge to study with an expectation of funding recommendations that have a realistic shot at passing as a ballot measure or legislation.

A state-based wildlife funding task force will generate enthusiasm, interest, and more groups joining in for an ultimate campaign.

Polling of Voters

One key action to help inform the state task force is to conduct a poll early in the campaign to secure wildlife funding. A poll can help determine:

- Level of support for wildlife;

- Level of support for outdoor recreation and other conservation-related issues like clean air and water;

- What funding mechanisms are popular and would be voted for;

- How much voters are willing to spend;

- Opposition, so you can address that up front.

Case Study

Wyoming: Governor’s 2015-17 Task Force on Fish and Wildlife

In 2015, Wyoming Governor Matt Mead established a task force “to develop a coherent strategy, including recommendations and measurable actions that the State can implement in order to broaden opportunities to effectively manage Wyoming’s fish and wildlife resources.”

image

Mead appointed 18 members, including the Wyoming Wildlife Federation (see list here). Mead announced the task force will “engage everyone who enjoys wildlife, not just hunters and anglers.” In 2017, the task force recommended that license, stamps, and permit revenues should fund programs that benefit game species; general fund appropriations should fund nongame species and other legislatively mandated programs; the Governor’s Endangered Species Act budget should be adjusted to prevent listings that could affect the state’s economy; and the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resources Trust should be fully funded.

Case Study

Oregon: 2015-16 Task Force on Funding for Fish, Wildlife and Related Outdoor Recreation

House Bill (2402) established a legislative task force to strengthen the ability of Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) “to carry out conservation and related outdoor recreation and education programs, maintain and enhance hunting and angling opportunities; and improve public access and habitat conservation programs.” The charge was to identify “sustainable, alternative funding to support those activities.”

The task force met its deadline of reporting to the legislature in September, 2016. The final report shows this committee of 17 worked diligently, conducted a statewide survey to learn what funding they would support and their impression of the state fish and wildlife agency. They took their ideas on the road, listened, and incorporated what they learned to come up with two funding mechanisms—one an Oregon income tax return surcharge and the other a wholesale beverage surcharge. The Oregon Conservation and Recreation Fund would bring in a minimum of $87 million a biennium and would be clearly allocated to expand conservation efforts, improve hunting and angling opportunities, connect Oregonians with the outdoors, and deferred maintenance.

The list of members of Oregon’s funding task force offers some potential ideas for your state—showing just how broad the spectrum can be to address all those with a state in the future of wildlife and outdoor recreation, including the travel and tourism industry, counties and tribal governments, the outdoor education community, and communities that may be “underserved or underrepresented.” The task force included state legislators. Both the ODFW director and the chair of the ODFW commission served on the task force as nonvoting members.

The task force recommendations led to a funding bill introduced by champion Rep. Ken Helm (chair of the House Interim Committee on Energy and Environment) in the 2017 legislative session. That bill was not voted on. A new bill was introduced in the 2019 session asking for $17 million in general funds for the biennium to the Oregon Conservation and Recreation Fund, as a temporary stopgap measure that would give the agency the ability to match its federal allocation based on passage of Recovering America’s Wildlife Act.

While it typically takes several runs at legislative and ballot initiatives before they are successful, it is important to work on creating a coalition and campaign ready to go upon the release of a task force’s recommendations. If not, then the work involved in fundraising and staffing and building a coalition will take up to a year and you will lose the momentum and power of the release of the recommendations. Many of these aspects can and should take place simultaneously.

2. Enlist state legislators and governor as champions.

To ensure the passage of your selected funding mechanism, you’ll need champions with influence and reach to promote its merits and help steer the campaign through obstacles. In fact, you may want to start with enlisting legislators and the governors first to establish a state funding task force.

In Virginia, the co-chair of the House Resources Committee Vick Thomas championed House Bill 38, a dedication of the state’s existing tax on outdoor equipment to a fund for wildlife conservation, and became a spokesperson for the need to conserve all wildlife, too. He raised the Assembly’s awareness of the need to fund Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, increasing key support for the mechanism and moving the process to success efficiently and quickly.

Identify Legislative Champions

To sleuth for potential legislative champions, check with your state fish and wildlife agency leadership to find out who is friendly to the agency and supportive of their requests.

Take a look to see who in your state is a member of the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators.

Look at the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation website to find hunting and fishing champions in the legislature as well as governors. Look up your state here.

Who’s on the Right Committee?

Find out who sits on key influential committees, like finance and natural resources. One of the obstacles you can run into is that the legislators who want to champion your cause are not on the committees that can putting forward such legislation. You will want to target those committee members—and find out what most moves them to support funding for wildlife, or make sure your champions have strong relationships on the committee(s). Remember, you can educate and enlist legislators that are not yet champions. Take them into the field where they can have a memorable experience with wildlife—like a million bats emerging at dusk to catch mosquitoes! Remember, you have the best ambassadors right at your fingertips- wildlife.

Meet with Governor and Key Legislators

The influential members of your coalition should set up meetings with the governor and legislators who will back wildlife funding. Use the power of your task force findings effectively. You will immediately have the attention of the governor if it’s a governor’s task force, and similarly the legislature, if it’s ordered by them. The key is to try to have the support of both entities no matter what.

Be Prepared—Messaging to Enlist Champions

While it’s a good idea to go to the champions early on in the funding campaign, you will get their full attention as you show them your developing coalition and public support. They will want to know who is for funding, both quantity and quality. Be clear on what you are asking for. Be specific with tangible examples. Avoid the trap of saying you want funding. Instead, you want to save wildlife in trouble and invest in a sustainable outdoor recreation economy. Funding is the mechanism.

Do your homework. Be aware of who else is competing for funding and see if you can be allies rather than competitors. Put yourself in the position of the governor being courted for funding from many sectors. How can you stand out and shine?

Before your meeting, research convincing messages that will resonate with a certain legislator or the governor. For example, if you know your governor’s number one issue is to boost the economy, then you might lead with this point:

- The best way to invest in our growing outdoor recreation economy (add stats) is to invest in a future for our threatened wildlife and the lands and waters both wildlife and recreationists depend upon. Put together powerful statistics in a way that combines the economic contributions together, as in this example from Colorado.

If a legislator or governor is a hunter or angler concerned about maintaining those traditions, you might lead with the fairness angle such as: After a century of shouldering almost all responsibility for our state’s wildlife, it’s time for the entire population to chip in if we are going to solve the wildlife crisis and continue our hunting and fishing traditions.

Another legislator or governor may be a hiker concerned only with access and adding trails or might be most interested in parks and clean water.

3. Lead campaign to secure state wildlife funding.

Armed with recommendations from a task force and your champions in place, it’s time to rollout the campaign to secure funding. Make sure you are ready, your coalition is in place, and you are elevating awareness of the wildlife crisis. Several past efforts focused on the task force without taking the time to build external support and/or have a campaign ready to go. You will want to launch the campaign as soon as a task force issues its report. Hold a task fork press event with fanfare to release the recommendations. Have your diverse coalition ready to inform members and galvanize them toward action. Use this report to create momentum. If you do not use a task force, then you should create another way to launch the funding campaign publicly.

Your campaign will be centered on assuring a future for the people in your state to enjoy wildlife and the precious lands and waters that support them. You will need to connect the dots from funding to outcomes—showing spending will be accountable and fulfilling the goals. Messaging that connects voters with what they care about is an essential ingredient. Do not miss this important step. For example, we know from numerous successful state funding initiatives that clean air and especially clean water are the most compelling messages, especially for urban voters. In fact, WATER was THE reason for most wins. For more tips that will help you convince influentials and voters alike please see the Trust for Public Lands Action toolkit on messaging.

You Will Have Help

In addition to the National Wildlife Federation and its state-based affiliates, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Trust for Public Lands (TPL) are committed to help states design, pass, and implement public funding through ballot or legislative measures. TNC and TPL have successfully led ballot and legislative campaigns in more than 20 states and localities that have resulted in more than 70 billion dollars for conservation. They win 90 percent of the time! Their campaign planning template can be tailored to your state.

TPL maintains an excellent database called LandVote that records all land, wildlife, and recreation measures by year—a way to get creative and see what works, at the city, county, and state levels.

We will not go into detail on a running a funding campaign here, since you can easily access the excellent toolkit with case studies from the Trust for Public Lands Action Fund. National Wildlife Federation also offers an overall campaign toolkit here. Instead, we offer a few key useful points, and examples for campaigns to secure state wildlife funding and other materials.

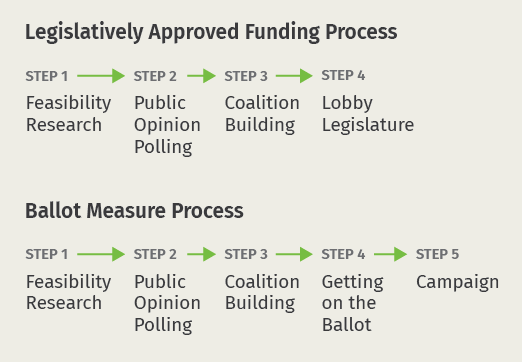

Legislative or Ballot Measure?

How your campaign goes forward depends on whether you have chosen a legislative or ballot initiative. A feasibility study, like what the Trust for Public Land regularly does, will help you evaluate your options. Below are some considerations.

Once you decide on your funding mechanism and route, you can make informed decisions on key partners and members of a larger coalition. Key conservation players will always be important, but depending on your funding mechanism, you will likely include others. Most successful campaigns addressed several funding needs, with water as most important. Remember your goal is to WIN. Compromise along the way is inevitable. If someone leading the key committee in the legislature wants funding for arts, then arts gets included as part of the package. You must make pragmatic decisions to ensure success.

Implementation is an often over-looked consideration. Anticipate your work after you win. You will need to defend your win. Funds are often targets to be raided or simply not spent. Sometimes initiatives are brought back to the ballot. Your coalition will need to keep fighting. Add defending the prize to your early planning as you build your coalition and support.

Learn from Missouri—A Continuing Model for Funding Success

In 1970, the Conservation Federation of Missouri began its campaign for dedicated funding for wildlife called Design for Conservation. Six years later, in 1976, Missouri voters passed a ballot measure establishing the Missouri Conservation Sales Tax. For every $8 in sale, one penny goes toward conservation. Note that the phrase “one penny…” is deliberate, showing just how little you pay for a big outcome.i

Time and time again, Missouri has defended its 1/8 of 1 percent sales tax against assaults. Since 2012, the sales tax has generated about $100 million each year. The programs remain popular and well supported—funding for wildlife and forest conservation and nature centers throughout Missouri. The money is consistent and growing to meet increasing demands. Wildlife is a public trust and all benefit, so paying in makes sense and gives all people a voice.

Keys to Success

Here are a few keys to success originally and today (adapted from 2017 observations of David Thorne, Missouri Department of Conservation):

- Citizen Support: The original funding initiative passed as a ballot measure of the people of Missouri. To assure that citizen support is rock solid and growing, the Missouri Department of Conservation reports to Missourians through outreach: that includes a free monthly magazine with more than 725,000 subscribers for a hard copy or online version. The Department also reaches out to youth with its Xplore Magazine.

- Listening to Missourians: The staff relies on what people in the state have to say about conservation—via comments, surveys, open houses, and public meetings. They use social media effectively-Facebook Twitter, YouTube, and a Blog. A service called GovDelivery sends email and text messages to those who request it.

- Urban, Suburban, and Rural Outreach: It took support from all those areas to pass the sales tax initiative with 50.8 percent voting yes in 1976. For the sales tax to pass, only 25 counties and the city of St. Louis had more than 50 percent voting yes—the counties where most of the Missourians live. The urban counties, similar to those counties voting yes, represent 73 percent of the population. In other words, the urban population is critical and must feel connected to the wildlife programs.

- Increased Investment in Hunter/Angler Programs: To answer concerns from anglers and hunters that expanded programming might reduce funding for their interests, the Department demonstrated that investments in their interests increases—not decreases—with broadened programming and increased funding.

- The Power of a Broad Coalition: Missouri has a powerful and successful wildlife coalition, because it is broad and inclusive. The coalition members are empowered, because they see their demands are met and show that people in Missouri are willing to pay to meet their wants and needs.

- Funding Links to Specific Outcomes: People in Missouri can see that the money that comes in via the sales tax goes to specific outcomes that are articulated in strategic plans. There are stated measures to evaluate success, determine progress, and accomplishments. The Department encourages transparency, as in this January 2018 annual report that calls attention to its responsibility to the public with the tagline: “Serving Missouri and You.”

- Design for Conservation a Firm Foundation: The original strategic plan was so well done that it laid a foundation for all that has followed, as well as fueling an excellent marketing and communication campaign.

- Brand Awareness: Prioritizing a Department “brand” that people know well helps citizens connect personally with conservation efforts, building ownership and pride.

Tips and more useful information for securing funding

Learn from Successful Funding Campaigns

To pass legislation or ballot initiatives to secure wildlife funding can take time and repeated efforts. You can learn from successful funding campaigns—that have strong coalitions and an educated, inspired public and leadership backing them.

Agencies are asked to do more with a shrinking funding base that is still primarily supported by hunter and angler user fees. Agencies need funding for all wildlife with a focus on preventing wildlife from becoming endangered, as well as meeting the increasing demand for recreation and education from a variety of constituents.

A temptation for wildlife leaders is to make the case for more funding without enough public support for why it’s needed and a coalition ready to campaign for it. Coalition building and choosing a funding mechanism for a campaign can go hand-in-hand. The funding campaign ideally should have the backing of the coalition, state wildlife agency leaders, the governor, legislators, and more.

Meeting the public where they are.

Message testing is an absolutely key ingredient. While wildlife tends to score high, water always is the highest. Water brings out all the voters. You want all those voters to vote on voting day.

Recent History of Coalitions and Funding Campaigns to Solve the Wildlife Crisis

From experience, we know that unified coalitions for wildlife and recreation can be powerful and effective at national and state levels. We’ve learned from experience and are becoming a more effective voice for change.

Teaming with Wildlife Coalition

In the 1990s, the national Teaming with Wildlife campaign was created to secure dedicated federal funding back to states to prevent wildlife from becoming endangered as well expanded recreation and education needs and opportunities. The original proposal would have applied the user fee model via an excise tax to an array of birding and outdoor-related recreation equipment. That would have extended user fees to many more people, relieving the burden on hunters and anglers, and moving closer to caring for wildlife as a public trust. More than 3,000 groups and businesses joined the Teaming with Wildlife coalition by 1998.

First Time Funds to States to Prevent Wildlife from Becoming Endangered

As interest in the legislation grew, members of congress switched the original user fee proposal to use existing oil and gas fees as more palatable than a “new tax.” The coalition grew to 5,000+ supporting $350 million annually needed for state wildlife conservation, recreation and education. The advocacy led to the establishment of the federal State and Tribal Wildlife Grants program. To qualify for funding, states developed State Wildlife Action Plans that are now the blueprint for conservation across the country. The plans have now created their own coalitions of support in many states.

Recovering America’s Wildlife Act Coalition

To address the growing wildlife crisis connected to lack of funding, the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act follows the recommendation of a diverse group of energy, business, and conservation leaders. This group, known as the Blue Ribbon Panel on Sustaining America’s Diverse Fish & Wildlife Resources, determined that an annual investment of $1.3 billion in revenues from energy and mineral development on federal lands and waters could address the needs of thousands of species, preventing them from needing to be added to the Endangered Species list. A growing coalition is forming around this federal bill, with some changes, that will send funds to states.

No Need to Reinvent the Wheel

The materials listed at the end of this section provide in-depth case studies on mechanisms for funding and strategies for successful campaigns. Several reports are particularly good overviews and offer recommendations including Investing in Wildlife: State Wildlife Funding Campaigns, and more recently the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Future Funding Mechanisms Study. Investigate how other funding campaigns in other states have succeeded, whether as ballot measures or as legislation. Learn from their coalitions and campaigns.

Additional Resources

Header photo credit: Ohio DNR